←

Thoughts after reading 10 PRINT.

→

I came to 10 PRINT CHR$(205.5+RND(1)); : GOTO 10

cold, having never heard of it until its arresting dust jacket caught

my eye at my neighborhood feminist

bookstore, in a bit of precisely

that serendipity the loss of which the partisans of the printed word

are always decrying. In this case they have a point. I doubt I’d have

come across this book without the bookstore taking a chance and

stocking it.

I’m glad I did. It’s an

improbable but fascinating exercise: a close reading of the titular

Commodore 64 BASIC one-liner, popular in the 1980s. The code uses that

computer’s PETSCII graphical

characters to draw a random maze similar to the one shown on the

book’s cover.1

I’m glad I did. It’s an

improbable but fascinating exercise: a close reading of the titular

Commodore 64 BASIC one-liner, popular in the 1980s. The code uses that

computer’s PETSCII graphical

characters to draw a random maze similar to the one shown on the

book’s cover.1

The first author (of ten!—apparently, the text was written and

edited collaboratively on a wiki) is Nick Montfort, known to me for

his interactive fiction authorship and

criticism, but perhaps better-known for

Racing the Beam (with

Ian Bogost, also a co-author of 10 PRINT), on the Atari Video

Computer System. I haven’t read that book, but the section on the

Atari VCS in 10 PRINT has piqued my interest, and it’s gone on my

list.

You might not think that there are 300 pages to be gotten out of a

38-character novelty program, and there are perhaps a few sections

which drag on a bit, but overall it’s a surprisingly rich book. There

are chapters on mazes, regularity, randomness, BASIC, and the

Commodore 64, as well as shorter sections punningly termed “REMs”

where the authors experiment with variations on the program (for

example, similar programs on other platforms and programs which

actually walk the maze).

Most interesting to me were the discussions of regularity and

randomness in art. In the twentieth century a number of artists began

to do work that prefigured algorithmic art, sans the computer. Artist

Vera Molnar described this era in a 1990 artist’s

statement

quoted in 10 PRINT:

To genuinely systematize my research series I initially used a technique which I called machine imaginaire. I imagined I had a computer. I designed a programme and then, step by step, I realized simple, limited series which were completed within, meaning they did not exclude a single possible combination of form. As soon as possible I replaced the imaginary computer, the makebelieve machine by a real one.

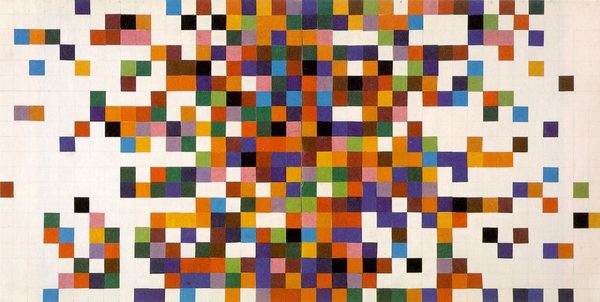

Randomness, too, interested artists such as Ellsworth Kelly, who used a system of matching numbers to colors and then choosing random numbers to populate a grid:

Kelly’s work inspired François Morellet, who in 1961 used a phone book as what a programmer might call a “source of entropy”:

With [Random Distribution of 40,000 Squares Using the Odd and Even Numbers of a Telephone Directory], the purpose of my system was to cause a reaction between two colours of equal intensity. I drew horizontal and vertical lines to make 40,000 squares. Then my wife or my sons would read out the numbers from the phone book (except the first repetitive digits), and I would mark each square for an even number while leaving the odd ones blank. The crossed squares were painted blue and the blank ones red. (François Morellet, 2009)

There’s much more in this book: richly-textured descriptions of the early days of the personal computer, when hobbyist software was distributed as source code listings to be typed in by hand, discussions of BASIC and the impact that its creators’ politics of accessibility had on its creation, a comparison of unicursal and multicursal mazes, and more.

As a programmer I too often think of code as pure instrumentality, its only interest deriving from its utility (with clarity and concision considered as a special case of utility). But of course code is not a natural feature of the universe. It is a human cultural artifact, no less so than a poem or a painting.

My thoughts here turn immediately to Lisp. (This will surprise no one

who knows me.) As a technological artifact Lisp has an unusually rich

cultural history. It is tied up with the genesis of the free software

movement; with the cold war

and its end; with the early

Internet (symbolics.com was the first commercial domain ever

registered, in 1985). The split between Lisp Machines, Inc., and

Symbolics over whether to bootstrap and maintain control or whether to

take outside venture capital prefigured a debate that continues

unabated within the tech world today. And Lisp post-Paul-Graham

remains a potent symbol of an alternative path, occupying far more

cultural space (“These are your father’s

parentheses”) than its current level of use

would seem to justify. More than anything, 10 PRINT made me

realize how much I want to read a similarly erudite cultural criticism

of Lisp.

As the book concludes:

Reading this one-liner also demonstrates that programming is culturally situated just as computers are culturally situated, which means that the study of code should be no more ahistorical than the study of any cultural text. When computer programs are written, they are written using keywords that bear remnants of the history of textual and other technologies, and they are written in programming languages with complex pasts and cultural dimensions, and they lie in the intersection of dozens of other social and material practices.

When we ignore this, we limit our understanding of our own work as programmers.

The full text of 10 PRINT is available

online as a PDF, but I recommend getting your

hands on a physical copy. The book is beautifully designed (by

co-author Casey Reas, one of the creators of

Processing), nicely printed, and full of

interesting screenshots and figures.

-

My intention was to embed the Javascript Commodore 64 emulator running the

10 PRINTcode at the top of this post; sadly, it’s very resource-intensive, slowing my rather-fast machine to a crawl. There is a faster Flash version, but life is too short to mess with Flash. ↩